New Firing Schedule: Controlled Cooling

Results and analysis is presented from current glazes fired with a controlled cooling schedule.

When the studio began operations in September 2022, a single firing schedule was adopted and used ever since. Given my knowledge of glaze production and kiln firing at the time, it seemed prudent to hold the firing schedule fixed and concentrate on other variables—especially when formulating new glazes using local granite.

Employing different firing schedules is not uncommon; in fact, it is an important skill to develop, since the way a glazed piece of pottery is fired will strongly affect its outcome—ideally in beautiful and creative ways.

There are two largely independent aspects related to firing. One aspect concerns the amount of oxygen present in the kiln, described as oxidation and reduction. Oxidation means the kiln environment is oxygen-rich during firing, while reduction means the environment is intentionally starved of oxygen. Electric kilns are not able to create true reduction atmospheres, so we are not concerned here with firing schedules that include periods of reduction.

The other aspect is the rate at which the kiln ramps up to its peak temperature—for example, 2232°F for canonical Cone 6—and the rate at which it cools after reaching that peak.

With respect to cooling, there are again two basic modes: turning the kiln off and letting it cool naturally (often called “natural cooling” or “no cooling”), or continuing to fire the kiln for a period in order to control the cooling at a rate more slowly than it would cool on its own (often called “controlled cooling” "cooling" or “down-firing”).

Up until now, the studio has used the same “no cooling” firing schedule, which ramps to its peak at varying rates and then shuts the kiln down once peak temperature has been reached.

The purpose of this article is to document initial experiments using a "cooling" firing schedule. The details of each fire schedule are documented here, including their parameters and references.

Motivation

While there remains much to learn about the granite glazes produced thus far, they are now well enough understood to begin to experiment with "cooling" firing schedules.

When the kiln reaches its peak temperature, the glaze is fully melted. In a “no cooling” schedule, the kiln is turned off and cools relatively quickly. This favors the formation of glassy glazes, since the glaze has little time to organize into crystalline structures as it cools. An analogy is obsidian, which forms when molten lava thrown from a volcano cools very rapidly, producing a natural glass.

In a “cooling” schedule, slowing the cooling process allows micro-crystals to precipitate from the glaze, changing its optical properties and often pushing a glassy surface toward a satin or matte finish. An analogy is the formation of granite itself, which begins as molten material deposited deep within the earth and cools slowly, allowing crystals to form under pressure over long periods of time.

Of course, the crystals formed in our kilns are different from those found in granite, since their chemical compositions and formation environments are quite different.

And you probably have seen glazes with large crystals present in the glaze. These are specially formulated glazes that take advantage of cooling schedules to allow for crystalline growth.

Results

Current studio glazes were fired without modification using a controlled cooling firing schedule. These glazes consist primarily of granite-based formulations, though several other frequently used studio recipes were included for comparison.

The granite glazes employ two related base formulations. Both begin with 70% granite and 30% wollastonite. Base-S (Silica) is produced by adding 10% silica, while Base-Z (Zinc) is produced by adding 4% zinc oxide in place of silica. (These formulations are presented unnormalized for clarity; when normalized, they correspond to Base-S at 64% granite / 27% wollastonite / 9% silica, and Base-Z at 67% granite / 29% wollastonite / 4% zinc oxide.)

Two cooling schedules were tested, each employing a controlled cooling rate of 150°F per hour. In Test 50 (T50), the kiln was turned off at 1700°F, while in Test 51 (T51), the kiln was turned off at 1500°F. These shutoff temperatures bracket key crystal-development windows for zinc- and iron-bearing silicate glazes, allowing comparison between a shorter cooling interval (T50) and an extended cooling interval that promotes greater micro-crystal growth and phase separation (T51).

The test matrix was intentionally broad rather than exhaustive. Not all possible combinations were explored, and some gaps in the data will therefore be apparent in the tiles presented below.

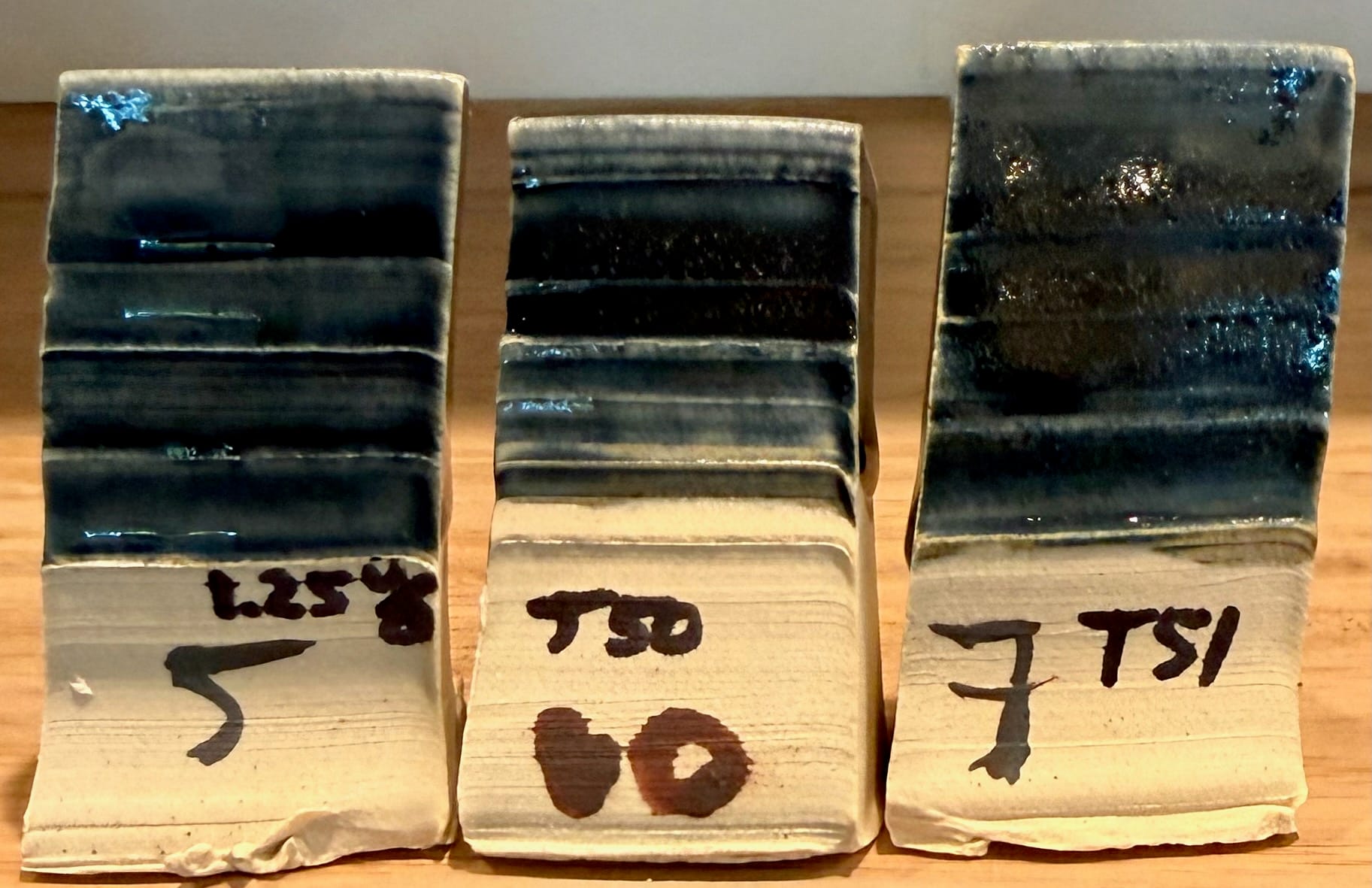

1) Mt Vision (MV) Tenmoku, Base-S and 8% Red Iron Oxide

- No Cooling: Tile T43-5 is Base-S with 10% red iron oxide fired using the standard no-cooling schedule. The glaze is fully melted and glassy, with localized micro-crystal formation visible in thicker areas. The addition of iron oxide acts as a flux in this otherwise satin-leaning base, increasing melt fluidity and promoting a glossy surface. Color development is strongest where the glaze is applied more thickly, consistent with iron’s role as a light-absorbing colorant whose effect increases with optical path length.

- Cooling: Tiles T50 and T51 use 8% red iron oxide and were fired with controlled cooling. Despite the slightly lower iron content, both tiles read as marginally richer in color and more mature in surface character. This is attributable to increased internal light scattering from enhanced micro-crystal development during cooling, which lengthens the effective optical path and amplifies iron absorption. Micro-crystals are more prevalent than in the no-cooling example, particularly in thicker areas, though the overall visual differences remain subtle.

Taken together, these results suggest that controlled cooling modestly enhances depth and surface maturity through increased micro-crystal formation, rather than fundamentally altering glaze character. All three variations remain fully usable, and fully glassy results can be achieved across firing schedules when glaze application is sufficient (see pottery below).

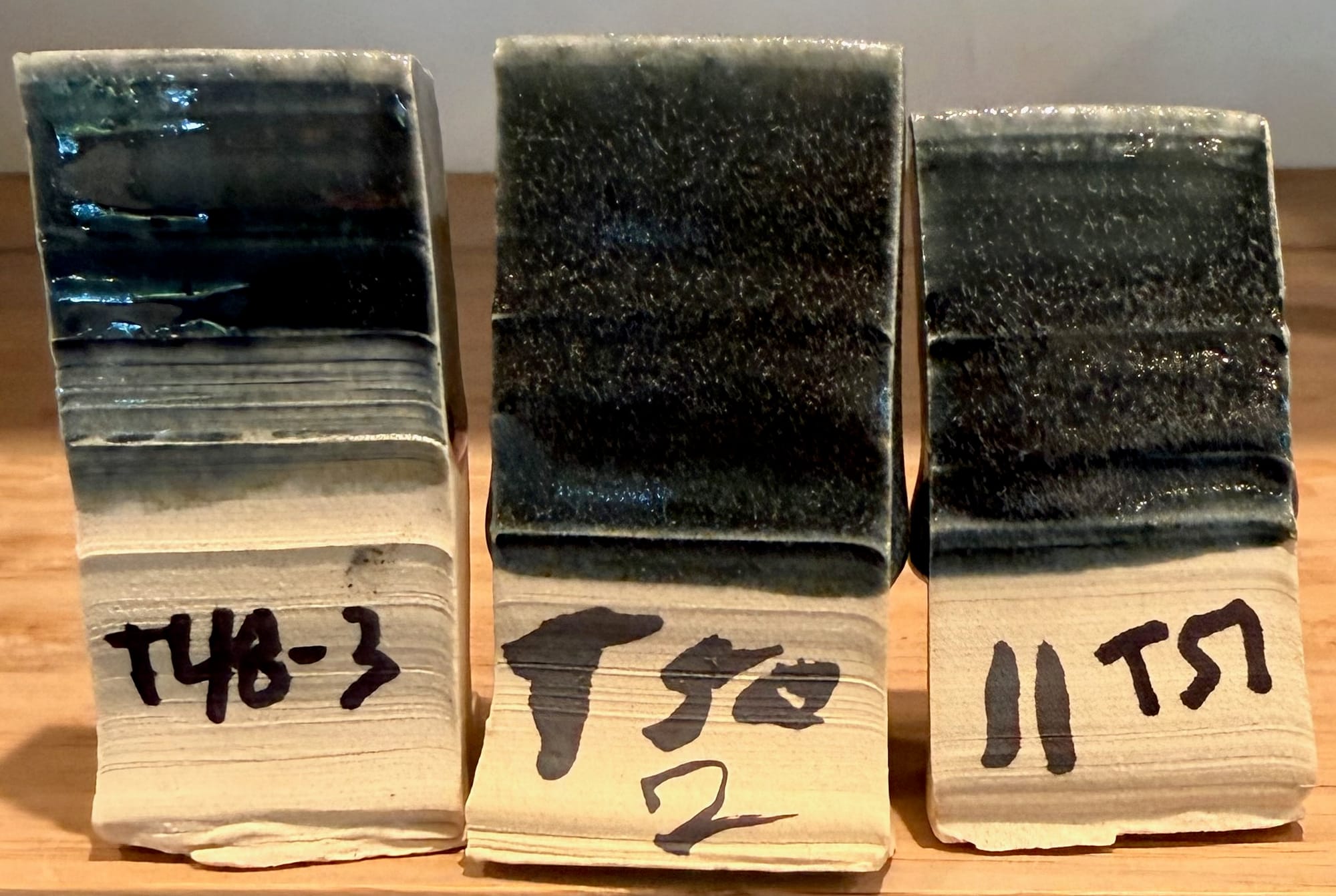

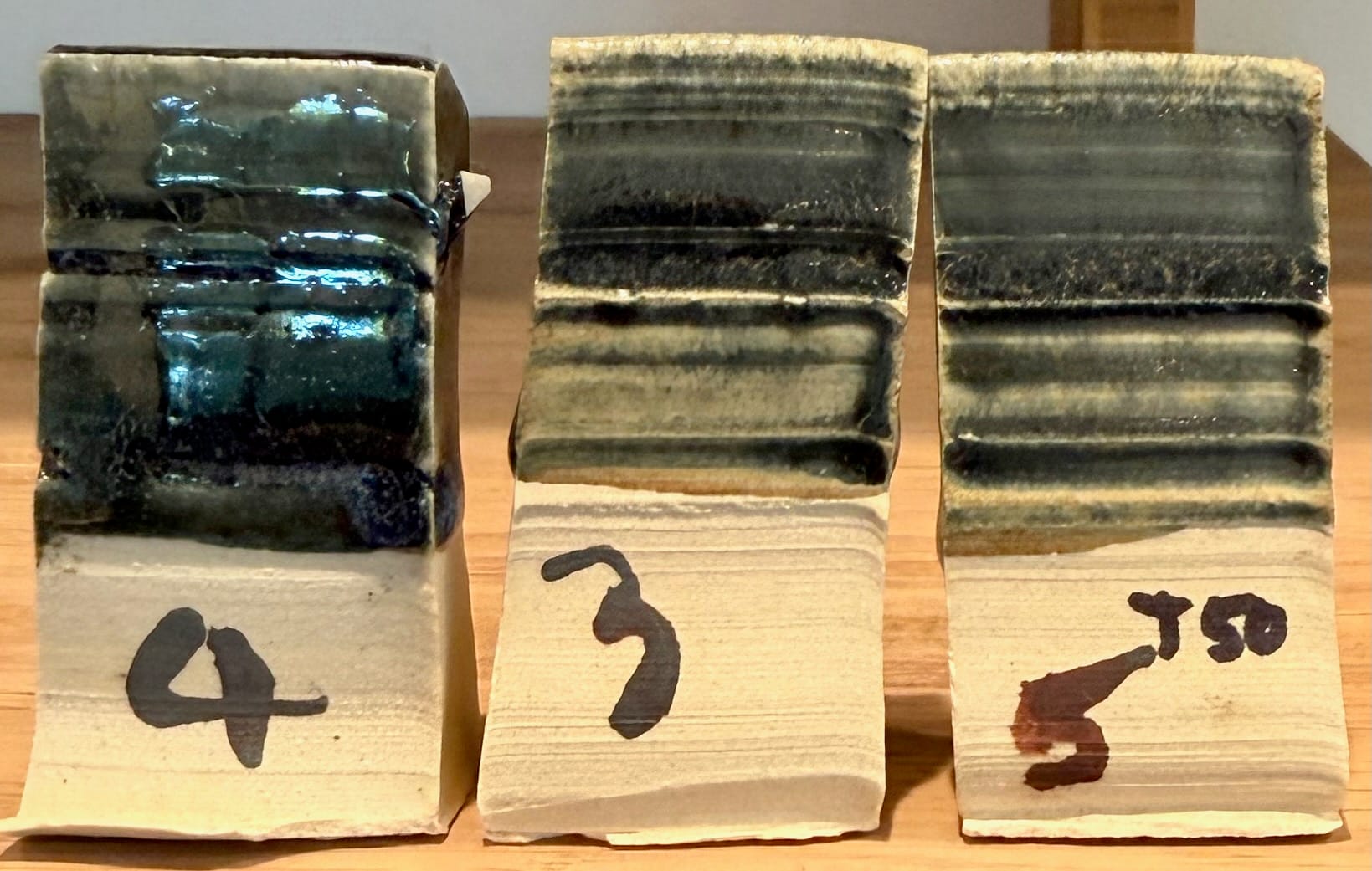

2) MV Zu Blue, Base-Z and 1% Cobalt Carbonate

- No Cooling: Tile T48-3 is Base-Z with 1% cobalt carbonate fired using the standard no-cooling schedule. The glaze is fully melted, glassy, and exhibits visible movement, reflecting the strong fluxing action of zinc in the base. Micro-crystal formation is minimal, and the surface remains optically open and glossy, allowing cobalt’s absorption to read cleanly through the glaze.

- Cooling: Tiles T50 and T51 use the same glaze but were fired with controlled cooling. In contrast to the no-cooling result, a dense micro-crystal matrix is clearly visible across both tiles. This crystallization scatters light strongly, shifting the surface away from gloss and toward a matte, increasingly dry appearance—most pronounced in T51, which experienced the longer cooling interval. The glaze also appears more fluid, with increased running, consistent with zinc-rich melts remaining mobile longer before crystallization locks the structure in place.

Overall, controlled cooling fundamentally alters the surface character of this glaze. Rather than subtly refining the finish, it pushes the zinc-rich system decisively toward crystallization, converting a glossy cobalt glaze into a matte, micro-crystalline surface. This highlights how sensitive Base-Z is to extended cooling through zinc-driven crystal-development windows.3) MV Inverness Gold, Base-S with no additives.

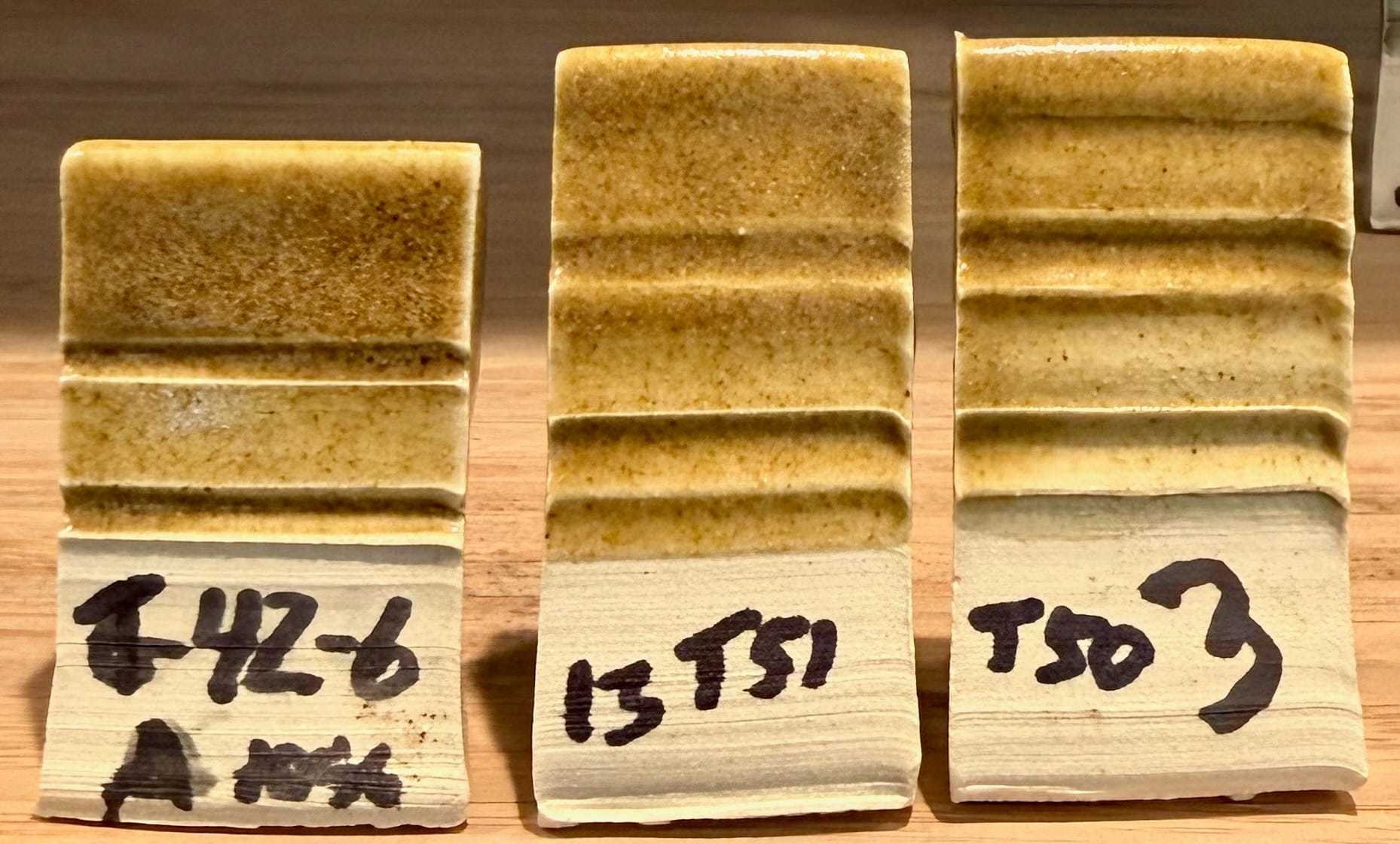

3) MV Inverness Gold, Base-S

- No Cooling: Tile T42-6 is Base-S with no added colorants or fluxes, fired using the standard no-cooling schedule. The glaze fires matte with warm honey tones and retains visible flecks of partially unmelted granite mica. Limited micro-crystal formation is present, but the surface remains relatively stiff, consistent with the higher silica content and absence of zinc in the base.

- Cooling: Tiles T50 and T51 use the same glaze fired with controlled cooling. Differences relative to the no-cooling result are subtle but perceptible. Both cooled tiles appear slightly softer in color and more mature in luster, with improved melt integration and reduced visual stiffness. Micro-crystal development is modestly enhanced, but not to the extent seen in zinc-bearing systems, and the glaze remains firmly within the matte range.

Overall, controlled cooling in this silica-rich, zinc-free base acts primarily as a refining influence, improving melt cohesion and surface softness rather than driving significant crystallization or dramatic shifts in finish. This contrasts strongly with Base-Z glazes, where zinc actively amplifies crystal growth during extended cooling.

4) MV Foggy Ocean, Base-S and 0.5% Cobalt Carbonate

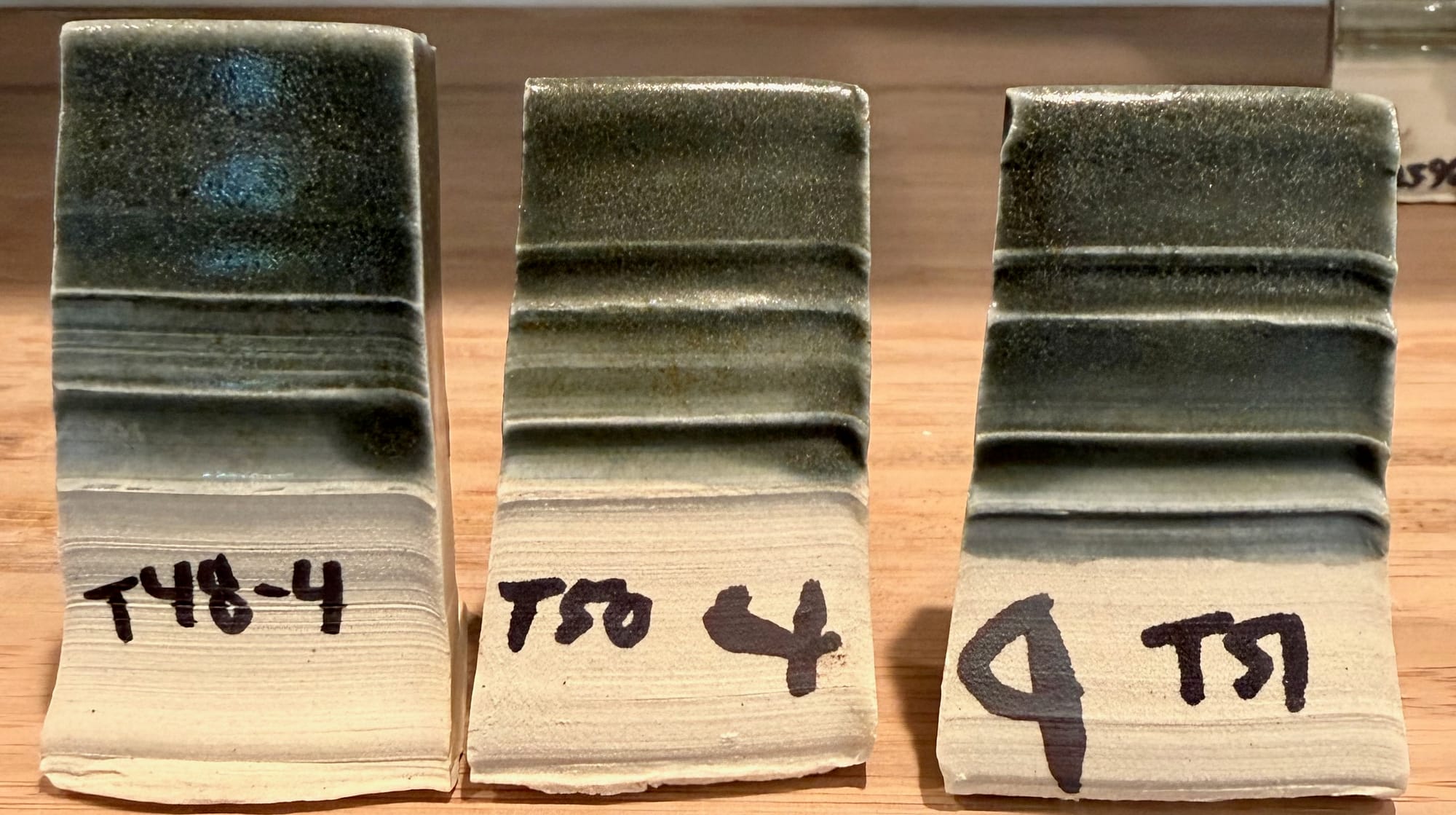

- No Cooling: Tile T48-4 is Base-S with 0.5% cobalt carbonate fired using the standard no-cooling schedule. The glaze fires matte and displays a range of blue–green tones that vary subtly with the natural iron content present in different batches of granite. In this silica-rich, zinc-free base, cobalt’s absorption establishes the blue component, while iron modulates the hue toward green where its influence is stronger. Micro-crystal formation is limited, and the surface remains optically open but structurally stiff.

- Cooling: Tiles T50 and T51 use the same glaze fired with controlled cooling. As with the no-cooling result, both tiles remain slightly matte, but the surface appears marginally more mature and cohesive. Micro-crystal development is modestly enhanced, contributing to a softer visual texture and more integrated color. The overall hue range remains similar, and the differences between cooling schedules are subtle rather than transformative.

In this case, controlled cooling acts as a refinement tool rather than a driver of major structural change. Without zinc to promote aggressive crystallization, the Base-S system responds to extended cooling with incremental improvements in surface softness and crystal development, while preserving its essential color character.

5) MV Celestial Blue, Base-Z and 1% Cobalt Carbonate and 4% Rutile

- No Cooling: Tile T46-1 is Celestial Blue, a Base-Z glaze colored with cobalt carbonate and rutile, fired using the standard no-cooling schedule. The glaze is fully melted and glassy, but when used alone it often lacks depth or nuance. Its strengths typically emerge when layered over other glazes, where interaction and thickness variation contribute visual interest.

- Cooling: Tiles T50 and T51 use the same glaze fired with controlled cooling. In contrast to the no-cooling result, both cooled tiles appear overdeveloped: the surface shifts away from gloss and becomes dry and overly crystallized. Extended cooling through zinc-driven crystal-development windows, combined with rutile’s strong nucleating effect, pushes the glaze beyond its optimal range when used on its own.

In this case, controlled cooling amplifies crystallization to the point of diminishing returns. While Celestial Blue remains effective as a layered glaze—where thickness variation and interaction can moderate these effects—it does not benefit from extended cooling when applied as a standalone surface..

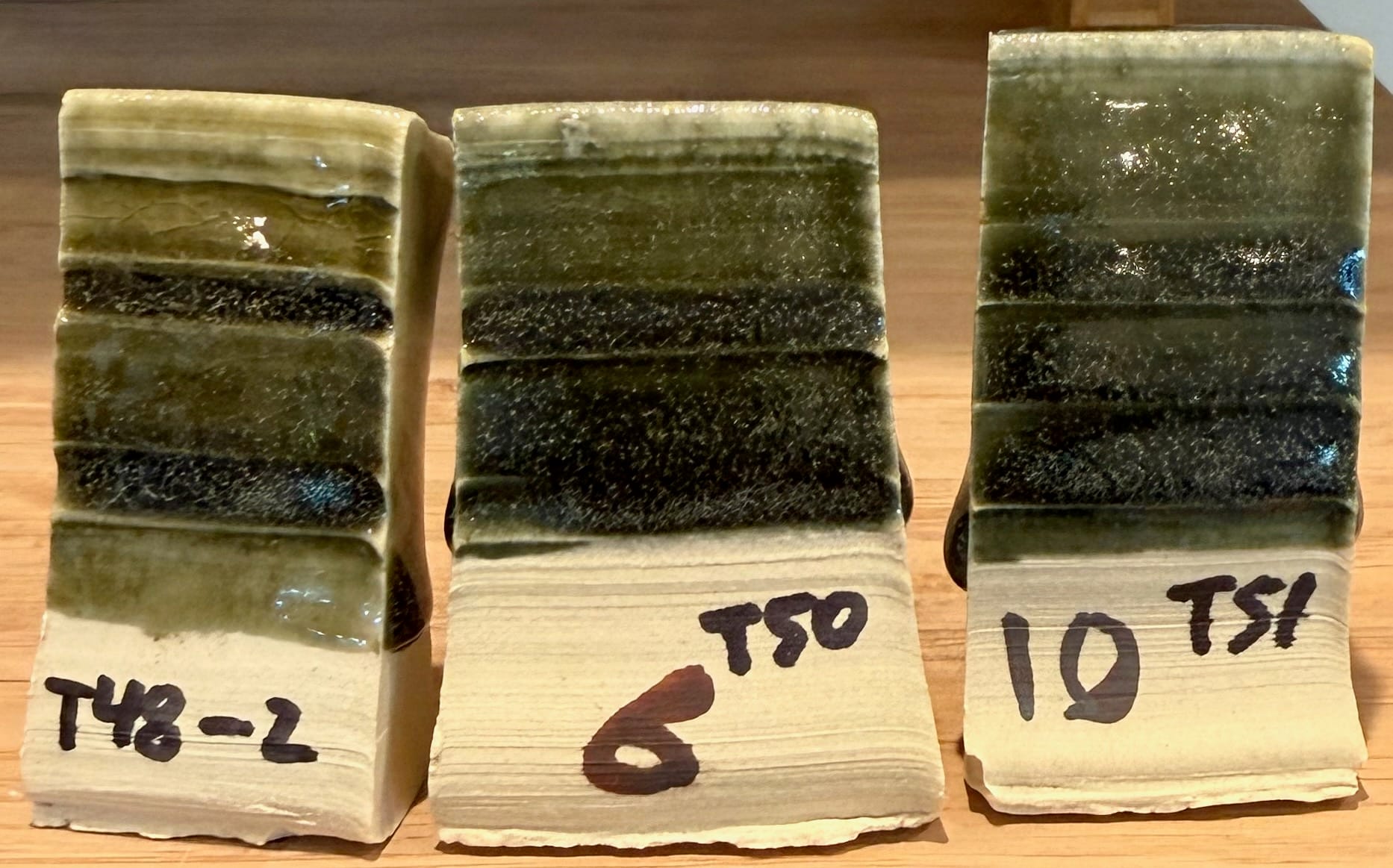

6) MV Green Celadon, Base-Z and 0.5% Cobalt Carbonate and 1% Red Iron Oxide

- No Cooling: Tile T48-2 is Green Celadon, a Base-Z glaze colored with cobalt carbonate and red iron oxide, fired using the standard no-cooling schedule. The glaze is fully melted and glassy, with visible micro-crystal development and strong depth of color. It clearly exhibits crazing, but visually it is already compelling, combining cobalt–iron green with the characteristic warmth and complexity of the granite base.

- Cooling: Tiles T50 and T51 use the same glaze fired with controlled cooling. While the overall color remains consistent with the no-cooling result, the surface becomes noticeably more active. Micro-crystals are more developed, and the glaze shows increased movement and visual depth, particularly in thicker areas. Rather than drying out, the surface retains its gloss while gaining complexity.

In this case, controlled cooling acts as a positive amplifier, enhancing micro-crystal formation and optical depth without collapsing the surface into matte or over-crystallization. The result is an increasingly expressive version of the granite Green Celadon, suggesting that this glaze sits near an optimal balance point for zinc-driven crystallization under cooling—despite the unresolved issue of crazing.

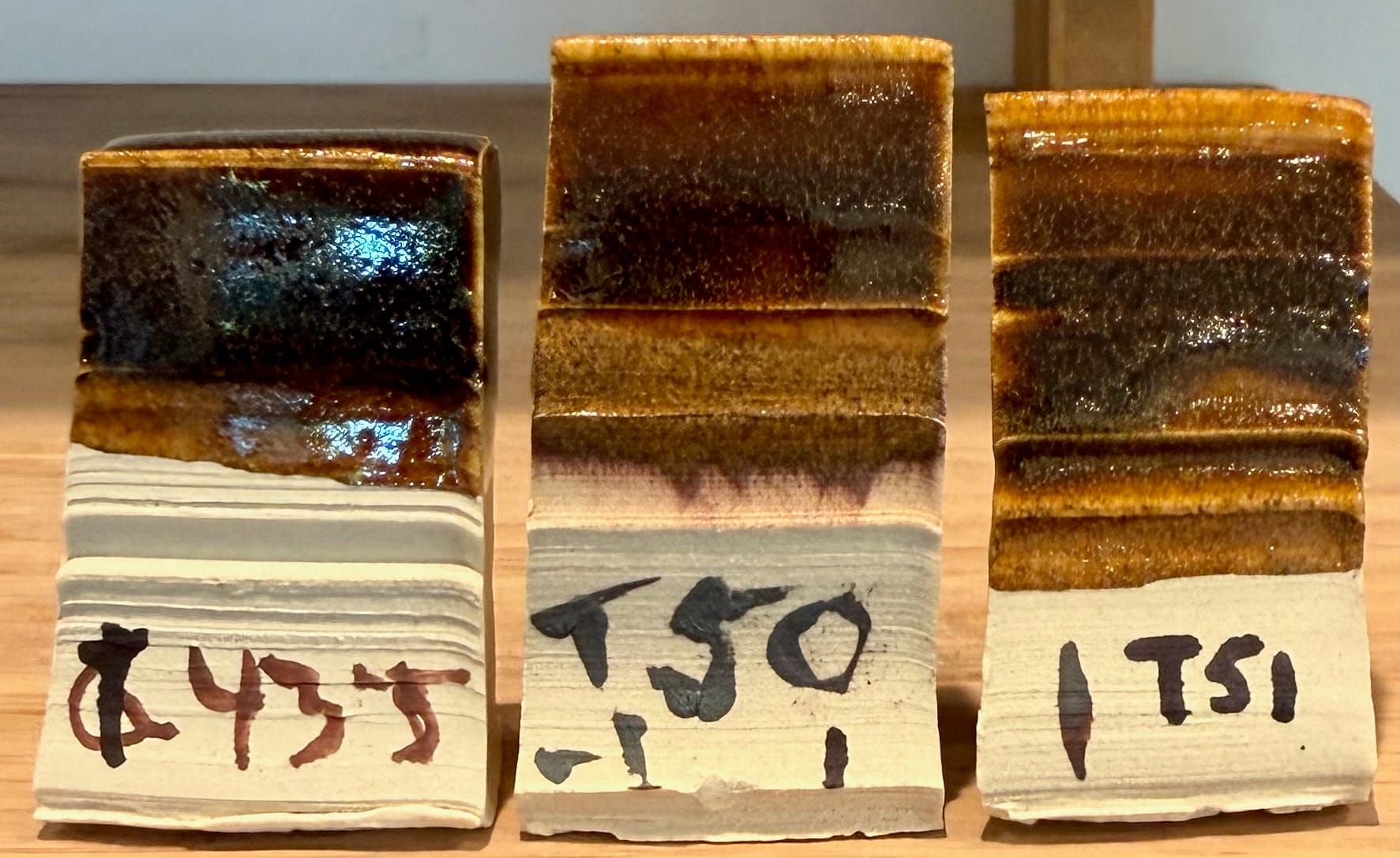

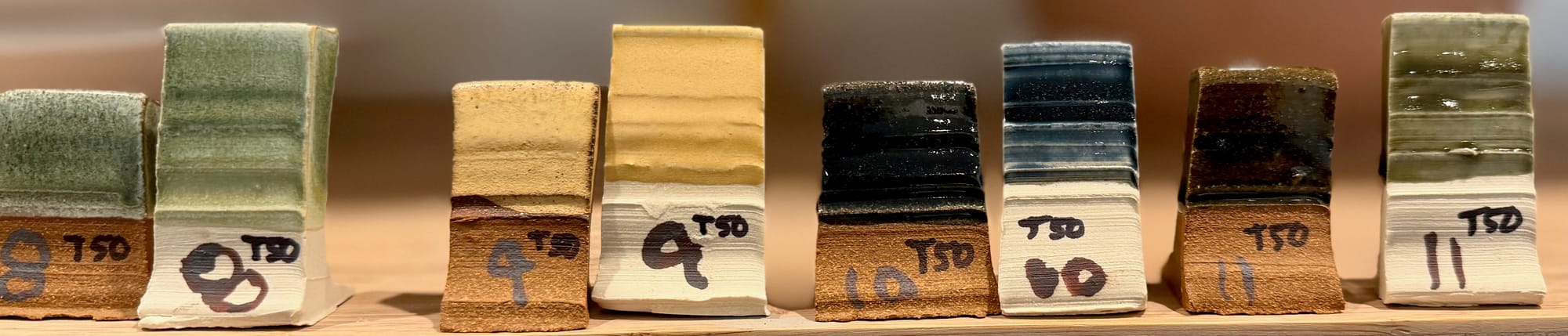

7) Kaki, from Britt (see T50 tiles above)

This glaze has never looked like advertised in the book and this example is no different. The recipe needs to be researched and remixed carefully or punt.

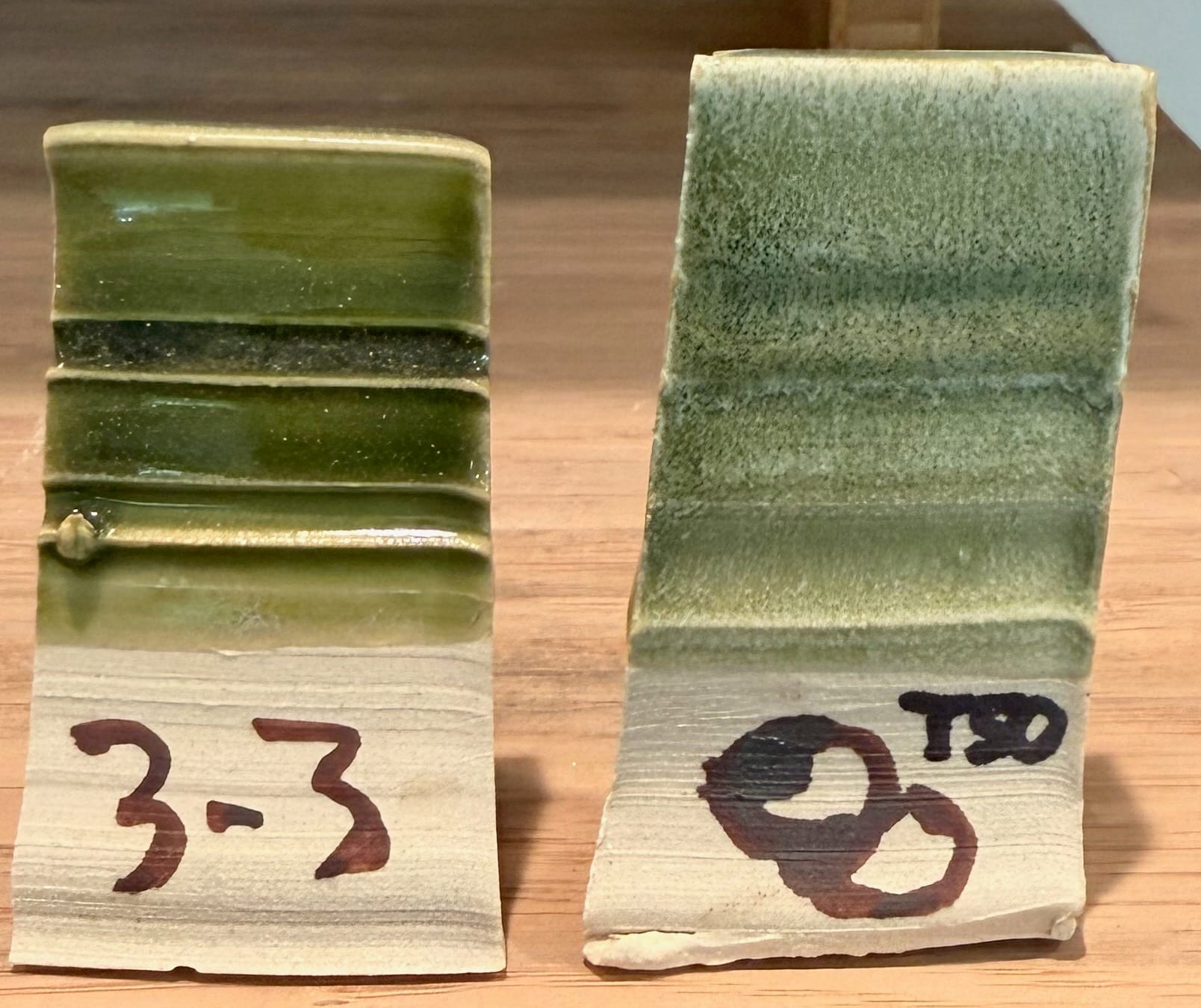

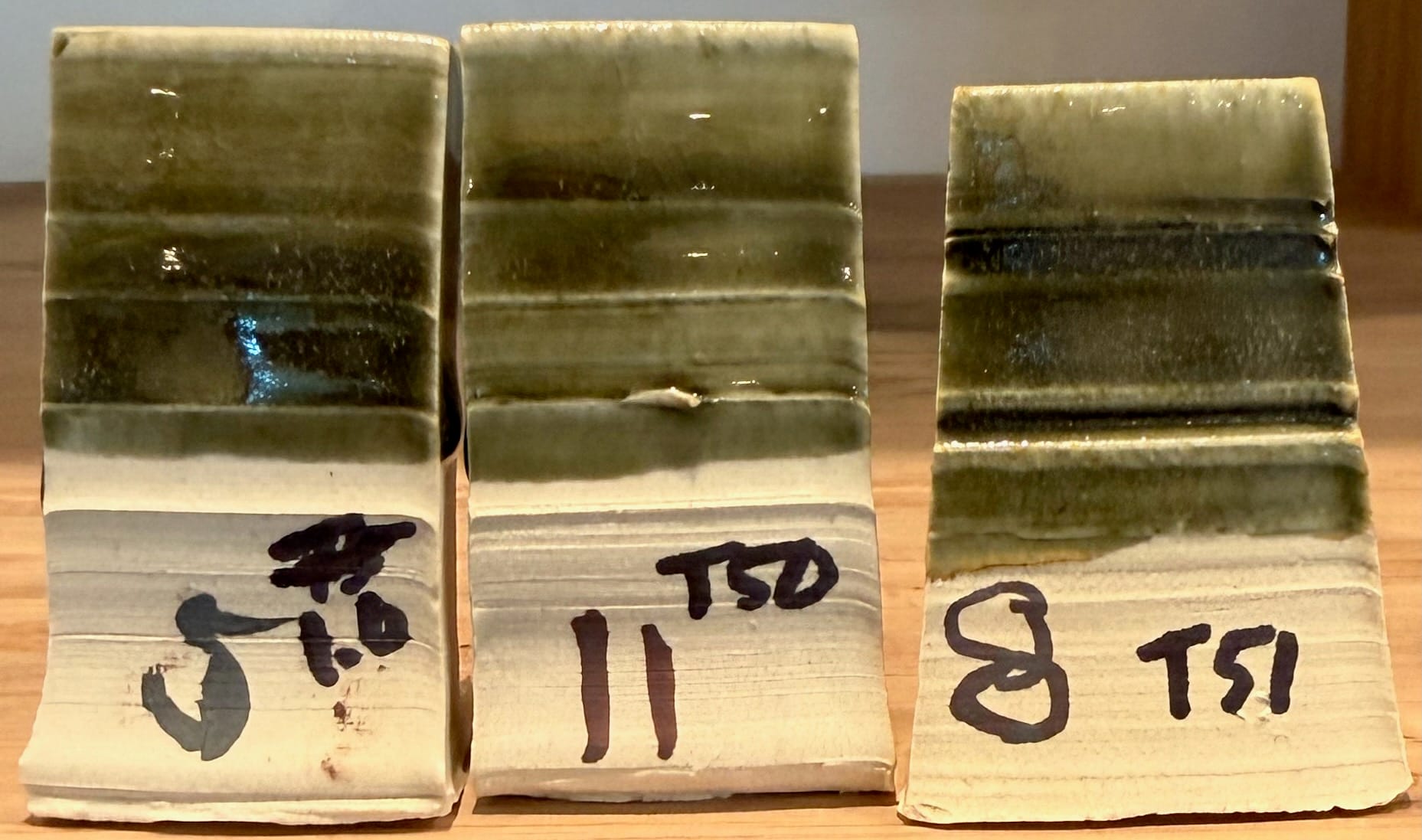

8) Spearmint, from Kline

One of the first glazes mixed at the studio, it's been a favorite non-granite glaze ever since. It's especially good layered on top of FM Matte White (from Britt).

- No Cooling: A consistent glassy, green glaze with some micro crystals that works on Porcelain and dark body clays.

- Cooling: The "cooling" result is dramatically different, exhibiting a satin Jade with strong white hues. This is a great find, though Kline does mention such a possibility in a footnote.

- No Cooling: More commonly we use Spearmint (from Kline) layered over FM Matte White (from Britt) because it softens the green and creates a cloudy look. It's especially good on dark body clays.

- Cooling: Here the "cooling" result is not so dramatically different and enhances an aqua color in the glaze while the consistency remains the same. Both work.

9) VC Matte Yellow from Britt

Also adopted by the studio early on, it's already matte with no cooling.

- No Cooling: A matte glaze by design, it needs a thick application to not be dry

- Cooling: Cooling makes it quite dry and unsuitable.

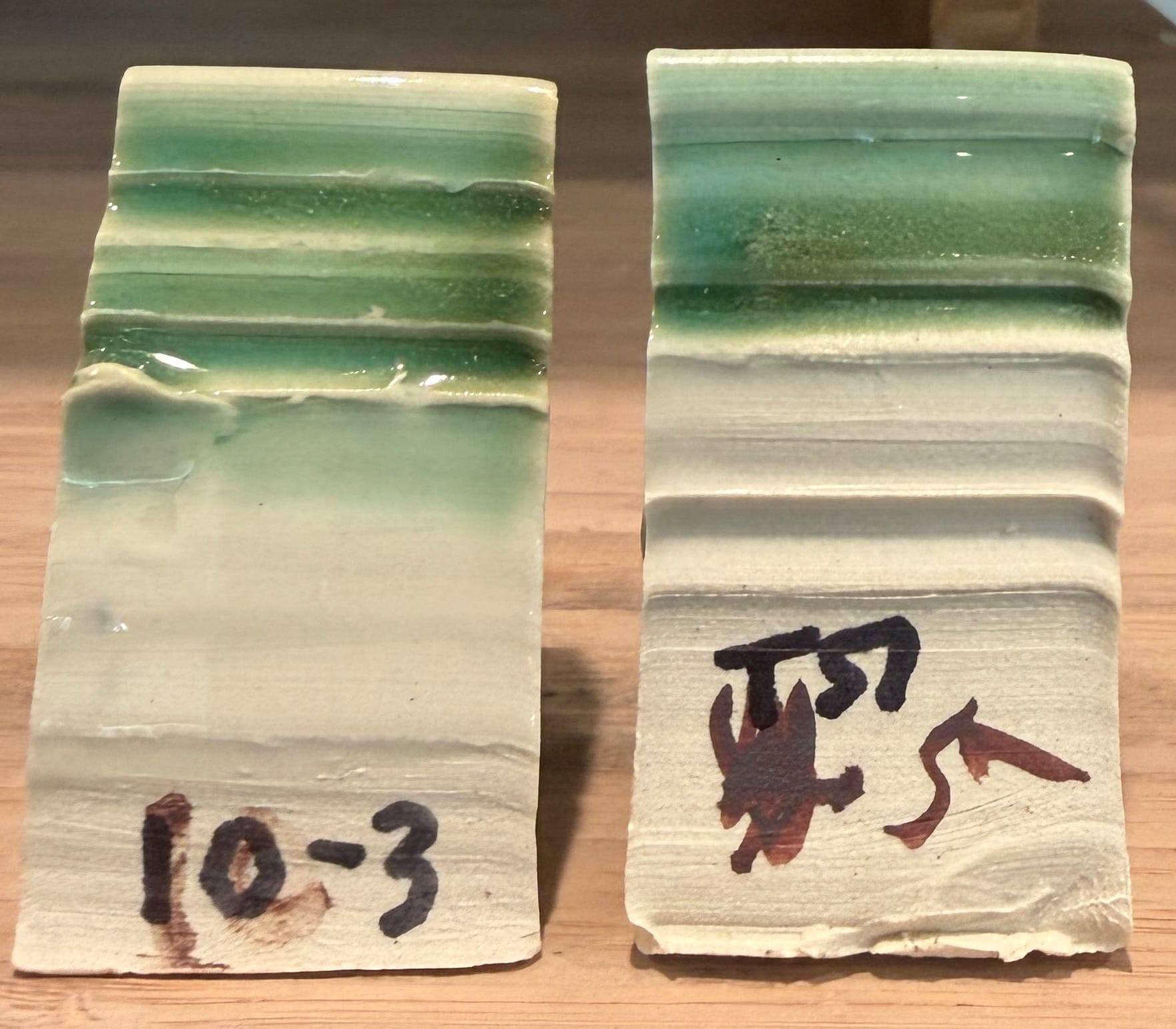

10) Base-Z, 1.25% Cobalt Carbonate and granite from Batch B

- No Cooling: Tile T49-3 is from a test line blend using the latest batch of granite (Batch B). The formulation matches Zu Blue, except cobalt carbonate is increased to 1.25% from 1%. Fired without cooling, the glaze is fully melted and glassy, and compares closely to earlier Zu Blue results made with the previous granite batch.

- Cooling: Tiles T50 and T51 use the same glaze fired with controlled cooling. Differences between the cooled tiles are modest but noticeable. Micro-crystals develop primarily in thicker areas, contributing to a slight loss of gloss and localized drying, most evident in T51, which experienced the longer cooling interval. Overall crystal development is less pronounced than in earlier Zu Blue tests using the previous granite batch, suggesting a subtle compositional difference in Batch B that reduces crystallization sensitivity under extended cooling.

In this case, controlled cooling does not significantly enhance the glaze and instead begins to push the surface toward dryness, particularly under the longer cooling cycle. The comparison highlights how small variations in granite composition can meaningfully influence crystal development and surface response under cooling, even when the base formulation remains unchanged.

11) Base-Z, 0.25% Cobalt Carbonate and 1% Red Iron Oxide

- No Cooling: Tile T49-1 is from a test line blend using the latest batch of granite (Batch B). The formulation matches Celadon Green, except cobalt carbonate is reduced to 0.25% from 0.5%. Fired without cooling, the glaze is fully melted and glassy, and reads noticeably lighter than the Celadon Green discussed above.

- Cooling: Tiles T50 and T51 use the same glaze fired with controlled cooling. Both remain well-melted and largely glassy, with modestly increased micro-crystal development—most apparent in thicker areas. Overall differences are minor, suggesting that this lower-cobalt celadon variant is less sensitive to extended cooling than the stronger cobalt version. As in other Batch B tests, T51 begins to show localized drying where the crystal matrix becomes dense, though the effect is subtle.

In this case, controlled cooling provides incremental gains in micro-crystal development without fundamentally changing the glaze, and the formulation appears to tolerate cooling somewhat better than the higher-cobalt Zu Blue variant under the same Batch B conditions.

The following is a test performed only in T51.

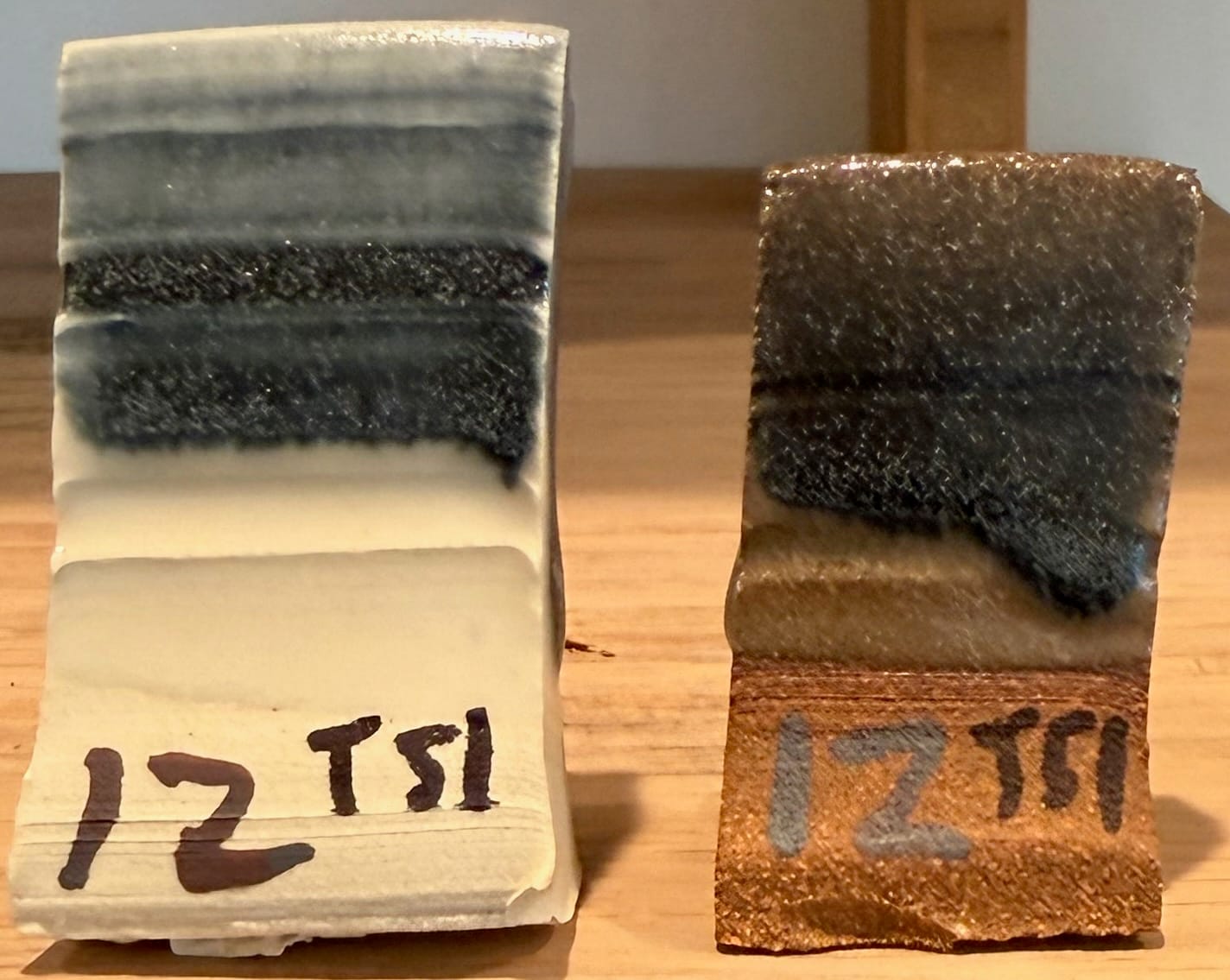

12) FM Matte White (from Britt) under Zu Blue, Base-Z and 1.0% Cobalt Carbonate

- No Cooling: Surprisingly, a no cooling test tile was nowhere to be found.

- Cooling: Tiles T51 for Nara-5 Porcelain and Sedona Red. As with the Spearmint over White example above, the FM Matte White softens the Zu Blue in pleasant ways. Where thin, the color remains a soft blue consistent with prior no-cooling results. At 1%, the cobalt dominates the natural iron as the color base. Where thicker, cooling strongly promotes micro-crystal development, producing a visibly textured surface. In the pottery example, the glaze is nearly rough—not from dryness, but from the extent of crystallization. A drawback is increased fluidity; the glaze is notably runny.

Real Pottery Examples

The results from T50 and T51 were encouraging enough to try the cooling schedule using pottery instead of test tiles. Examples cooled to 1500 degrees Fahrenheit are shown below:

1) MV Foggy Ocean on Nara-5 Porcelain

The Base-S + 0.5% Cobalt Carbonate produces a smooth matte glaze that exhibits micro crystals and a green-blue hue. The green comes from a sensitive interaction of the iron in the granite and the cobalt and the outcome is always at least slightly different.

2) Spearmint from Kline on Nara-5 Porcelain

A very stable glaze it moves from a darker, glassy green glaze under no cooling to a remarkably different lighter, matte green glaze with cooling. This was a happy find and a keeper (going back to Kline, he does mention this outcome is possible in a footnote).

3) MV Tenmoku on Nara-5 Porcelain (below) with Celestial Blue pooled on the bottom and then poured out

The Tenmoku remained smooth and glassy and looks much like it does when fired with no cooling but perhaps just a bit richer and more mature. Micro crystals develop where applied thicker. The Celestial Blue performed well layered on top and is also glassy with micro crystals where thinner and tending towards matte where thicker. It exhibits a green-blue where it ran and its typical cloudy blues and whites where it pools.

4) MV Celadon Green on Nara-5 Porcelain

This is the Base-Z with 0.5% Cobalt Carbonate and 1% Red Iron Oxide. It remains glassy, breaks nicely, has movement and micro crystals where applied thicker. A solid glaze.

5) MV Zu Blue on Nara-5 Porcelain

In this instance an even, satin glaze was achieved by dipping. In addition to being uniform, abundant micro crystals were developed, but not overly developed. Due to the micro crystals, the blue color is a bit darker than similar pieces fired with no cooling.

6) MV Zu Blue over FM Matte White (from Britt) on Nara-5 Porcelain

A go-to glaze combination with no-cooling, it turns matte under cooling due to heaving crystal development, so much so, it's rough to the touch where thick. It's also runny, nearly ruining these pieces. These pieces were dipped in each glaze and therefore had an abundance of glaze on them.

7) MV Inverness Gold (Base-S) on Nara-5

With cooling, this glaze seems just a bit more mature and silky-satin than with no cooling. Both work, but this is better.

In Search of a Honey Cream

The working hypothesis for this series was to take the granite Base-Z glaze and explore the use of titanium dioxide and Zircopax (zirconium silicate, ZrSiO₄)—both opacifiers—under a controlled cooling firing schedule, to see whether a suitable honey-cream glaze could be achieved. Working against this goal is the natural iron content of the granite, which imparts a strong honey coloration to the base glaze.

Test T53-3

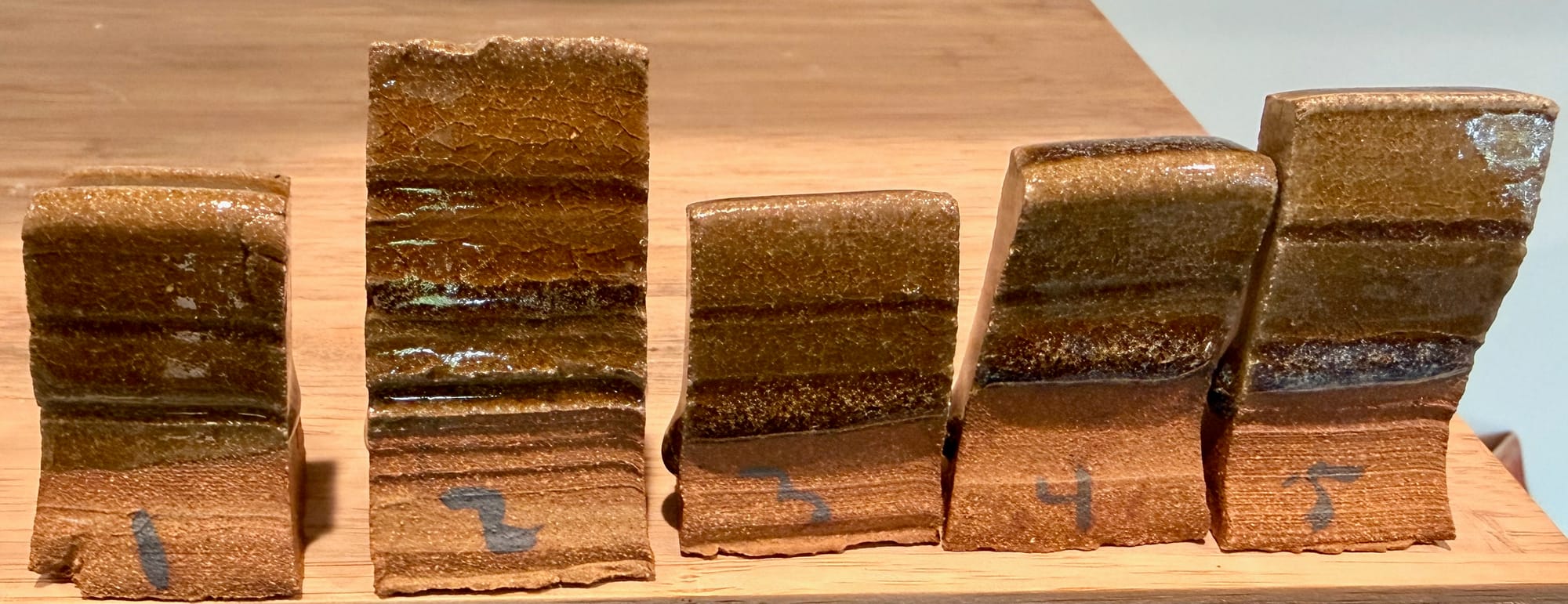

In this test (below), titanium dioxide was varied in 1% increments, producing samples at 0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, and 5%.

As the glaze cools, titanium dioxide promotes both micro-crystal formation and phase separation, in which the melt separates into chemically distinct glassy regions. The resulting internal boundaries scatter and refract light, increasing the apparent opacity of the glaze.

At 3%, 4%, and 5% TiO₂, visible micro-crystal development becomes apparent, particularly in thicker areas of application. In these regions, a corresponding darkening of the glaze is observed. This darkening reflects an optical intensification of the underlying honey color produced by the iron already present in the granite, driven by increased internal scattering and longer effective light paths created by the newly formed microstructures. However, despite increased opacity and surface activity, these additions did not produce the uniformly opaque, creamy–satin surface originally sought.

An additional and more subtle effect can be seen on tile #5 (below).

Where the glaze is thickest, most notably at 4% TiO₂, an opalescent blue variegation is observed. This effect arises from selective light scattering by titanium-derived microstructures formed during cooling, which preferentially scatter shorter (blue) wavelengths of the visible spectrum.

The opalescent blue variegation is more pronounced on iron-rich clay bodies such as Sedona Red (below). Reduced back-reflection from the darker body, combined with trace iron contribution at the glaze–body interface, enhances internal light scattering and deepens the effect. On porcelain, strong white back-reflection suppresses this behavior, making the opalescence noticeably less apparent.

The detail of tile T53-3 #5 is shown above. The opalescent blue variegation is an attractive feature.

Intrigued, the glaze corresponding to tile T53-3 #5 was applied to a small porcelain cup (above). The glaze is a pleasant golden-amber and the blue variegation appears again where it pools, it exhibits movement and has a glassy finish. The glaze was brushed with three coats. Clearly something when wrong in the center. On the cups exterior, the glaze was brushed applied too thin (and / or the clay body was still wet) and the glaze came out matte and dry.

Test T53-4

The final line test (below) uses granite Base-Z with 2% titanium dioxide, corresponding to tile #3 in Test T53-3. Zircopax was then varied in 1% increments, beginning at 4%, producing test tiles at 4%, 5%, 6%, 7%, and 8%.

In contrast to titanium dioxide, Zircopax opacifies by remaining largely undissolved in the glaze melt, scattering light as inert, high-refractive-index zirconium silicate particles rather than forming cooling-dependent microstructures.

In the granite Base-Z glaze containing 2% TiO₂, the lower-zircon tiles retain visible titanium-derived microstructures formed during cooling, similar to those observed in the previous test. As the proportion of Zircopax increases, the glaze becomes progressively cloudier as zircon particles increasingly dominate light scattering. At the highest zircon levels, these particles effectively obscure the underlying TiO₂ microstructures, shifting the surface toward a cream-satin appearance in which the original crystalline activity remains present but is largely optically masked.

On Sedona Red, opacity is enhanced, and by 8% Zircopax an almost caramel surface is achieved—likely because the darker, iron-bearing body reduces back-reflection and deepens the tone of the now more light-scattering glaze.

While these glazes are moderately compelling, the tests indicate that achieving a true honey-cream glaze from the granite likely lies elsewhere. This may involve reducing the zinc content of the base, lowering the percentage of granite to reduce iron content, or—more likely—adjusting both together.