Revisiting Copper

Experimental results that use the granite glaze with Copper Carbonate as a color enhancer are presented.

Very early on a few tests were made using the granite base glaze and Copper Carbonate (documented here). These experiments employed large quantities of Copper Carbonate (1% - 5%) and produced metallic glazes that were more curious than beautiful.

This time, rather than use copper as a main colorant, the approach is to use small amounts of Copper Carbonate (<= 1%) as a color enhancer.

Copper Carbonate as a Color Enhancer

A series of line blends were conducted that varied copper carbonate by 0.25% increments giving test tiles of 0%, 0.25%, 0.5%, 0.75% and 1.0%.

For each test, Base-Z was used, which is the zinc-based granite base formulation of 70% granite, 30% Wollastonite and 4% Zinc Oxide (normalized 67%/29%/4%). The granite came from new batch, Batch B, which to date is largely untested. A no cooling firing schedule was selected.

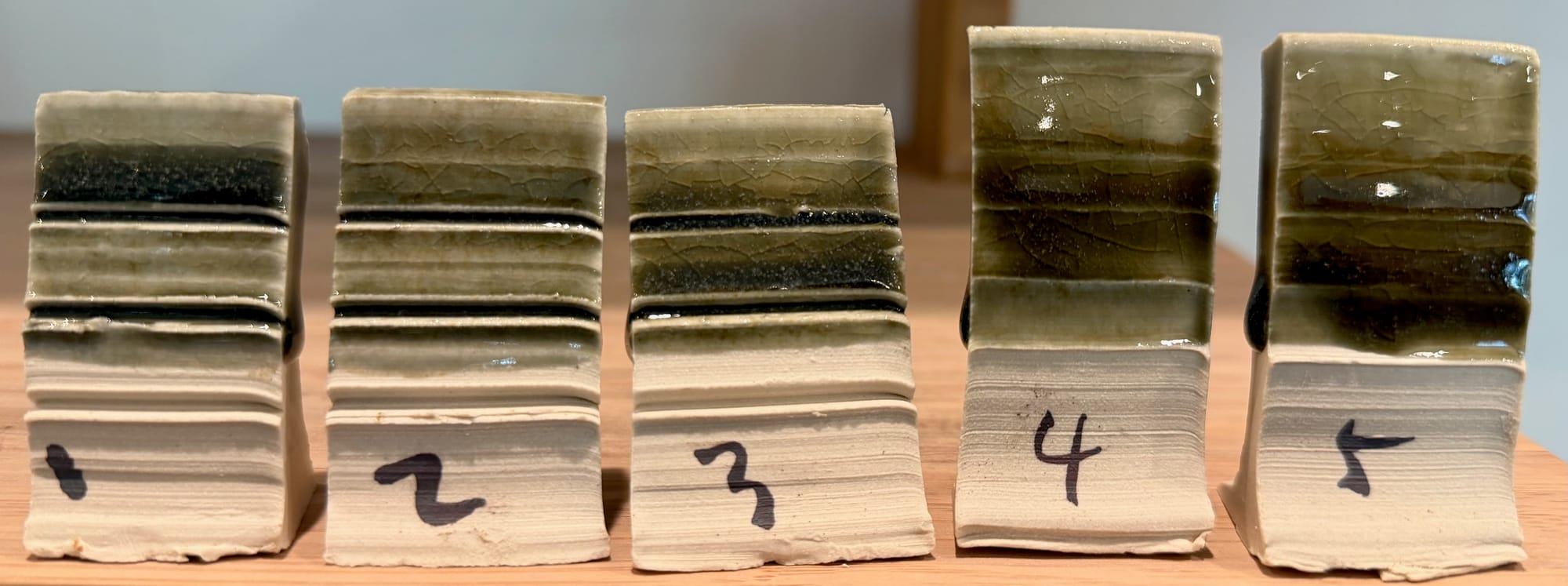

Test T52-1: The line blend for the natural Base-Z glaze is shown below.

Tile #1, with no copper added, produces a glassy, fully melted, honey-colored glaze; even the granite micas are completely dissolved. The coloration arises from the natural iron content of the granite.

Iron imparts color primarily through selective absorption of light, with thicker areas appearing darker as the optical path length increases. During cooling, micro-crystals form within the glaze, with trace titanium present in the granite acting as a nucleating agent for silicate crystallization—primarily zinc-bearing silicates in this zinc-rich base, and iron-bearing silicates in silica-rich systems such as Base-S. These micro-crystals scatter light within the glaze, further increasing the effective optical path length and thereby enhancing iron’s absorptive effect.

The addition of copper carbonate did not introduce blue or green hues in the granite Base-Z glaze, as might otherwise be expected. Instead, copper acted to deepen and enrich the existing honey coloration, indicating that iron—introduced through the granite and present at sufficient concentration—remains the primary optical driver in this system, governing light absorption and dominating the visual response of the glaze. Copper contributes by overlapping iron’s absorption bands and increasing internal light scattering, effectively warming the glaze without shifting its hue. Although crazing is clearly present, the results remain compelling, and any of these tiles could form the basis for further glaze development.

Interested to see more, the glaze from T52-1 #5 was applied to a porcelain cup (above). The result on the inside of the cup is a glassy glaze with a deep honey-amber or perhaps caramel hue that has beautiful moment and darkens with micro crystals where pooled. In this example, the glazed was brushed and some type of defect occurred in the middle, mostly likely it was simply left thin by accident. Similarly, on the outside the glaze was applied too thinly and became matte and dry.

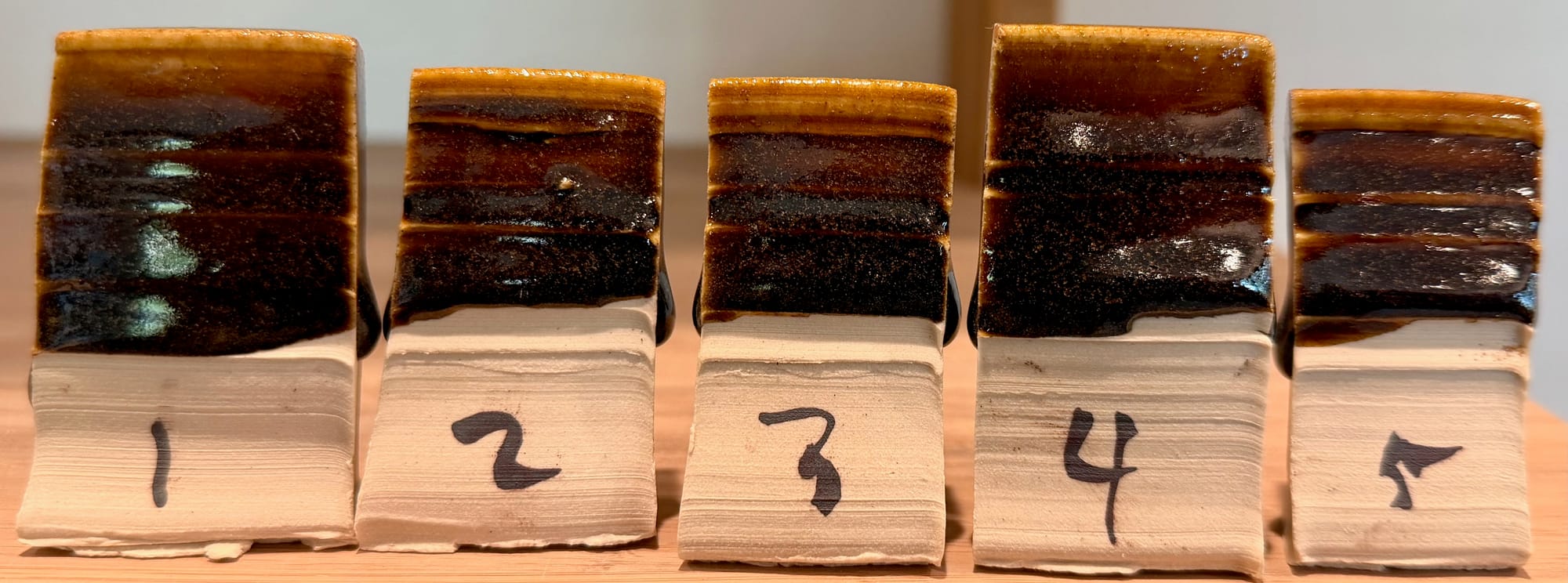

Test T52-4: The line blend below begins with Base-Z plus 8% Red Iron Oxide.

Tile #1, with no copper added, is noticeably darker and more brown in tone than in T52-1 due to the increased iron content. As copper carbonate is introduced in subsequent tiles, the glaze shifts from brown toward a richer amber hue, producing a subtle but pleasant warming effect. The underlying optical mechanisms remain the same as in earlier tests, with iron acting as the primary optical driver and copper functioning as a secondary modifier.

Notably, this formulation does not exhibit crazing. This is likely due to the addition of iron, which leads to a reduction in glaze thermal expansion and an increase in glass stiffness, improving the glaze–body fit..

Intrigued for more, glaze from T52-4#5 was applied to a small porcelain cup (above). The glaze was poured on the inside and brushed on the outside. The result is an attractive warm, deep amber that is almost black where pooled at the bottom, and shows a hint of green on the lip where thinest. The glaze is glassy and shows no crazing. On the outside of the cup, however, the brushed portion had too little glaze and turned matte and dry in comparison.

Test T52-2: The line blend below begins with Base-Z plus 0.25% cobalt carbonate.

Cobalt carbonate is a very strong colorant and, at sufficient levels, will quickly dominate the visual contribution of the granite’s natural iron. Like iron and copper, cobalt imparts color through selective absorption of light, preferentially removing longer wavelengths and allowing blue light to pass.

Even at 0.25%, tile #1 (with no copper added) exhibits subtle blue-green hues, particularly in thicker areas of the glaze. These tones arise from the overlap of absorption bands between cobalt and the natural iron present in the granite, rather than from cobalt acting alone. With increased cobalt content, this overlap would eventually give way to a fully blue glaze.

As in previous tests, micro-crystal formation enhances absorption by increasing internal light scattering and optical path length. At this relatively low level of cobalt carbonate, the addition of copper shifts the color balance: thinner areas move toward greener tones, while thicker areas deepen toward a darker green-brown, reflecting the continued dominance of iron absorption where optical path length is greatest.

None of these tiles are particularly interesting with the exception of tile #3. Normally 0.5% Cobalt Carbonate is used; so perhaps that scenario should be tested.

Test T52-3: The line blend below begins with Base-Z plus 0.25% cobalt carbonate and 0.5% red iron oxide. For reference, the standard MV Celadon Green uses 0.5% cobalt carbonate and 1% red iron oxide and produces a significantly darker green. This test explores the use of copper in a lighter variant of that celadon system.

As discussed previously, the observed blue–green tension in these glazes arises from competing absorption bands between cobalt and iron: cobalt suppresses longer wavelengths while iron absorbs shorter wavelengths, leaving a narrow blue–green window whose expression varies with glaze thickness and internal light scattering.

In this case, the glaze reads as a light green where thin and shifts toward brown hues where thicker. At these levels of cobalt and iron, the addition of copper appears largely inert, producing little meaningful hue modification. The result is a muted olive tone that lacks visual depth and is ultimately not very compelling.

In Search of a Black “Tenmoku”

These experiments build on the previous tests but move into a richer and darker range of color. The working hypothesis was to take the MV Tenmoku base and introduce variations of copper and cobalt in an effort to tease out a very dark—or black-ish—satin glaze using the new cooling firing schedule.

Two tests were conducted using Base-Z with 10% red iron oxide. As is often the case in glaze development, the results diverged from what was initially expected—or perhaps more accurately, from what was hoped for.

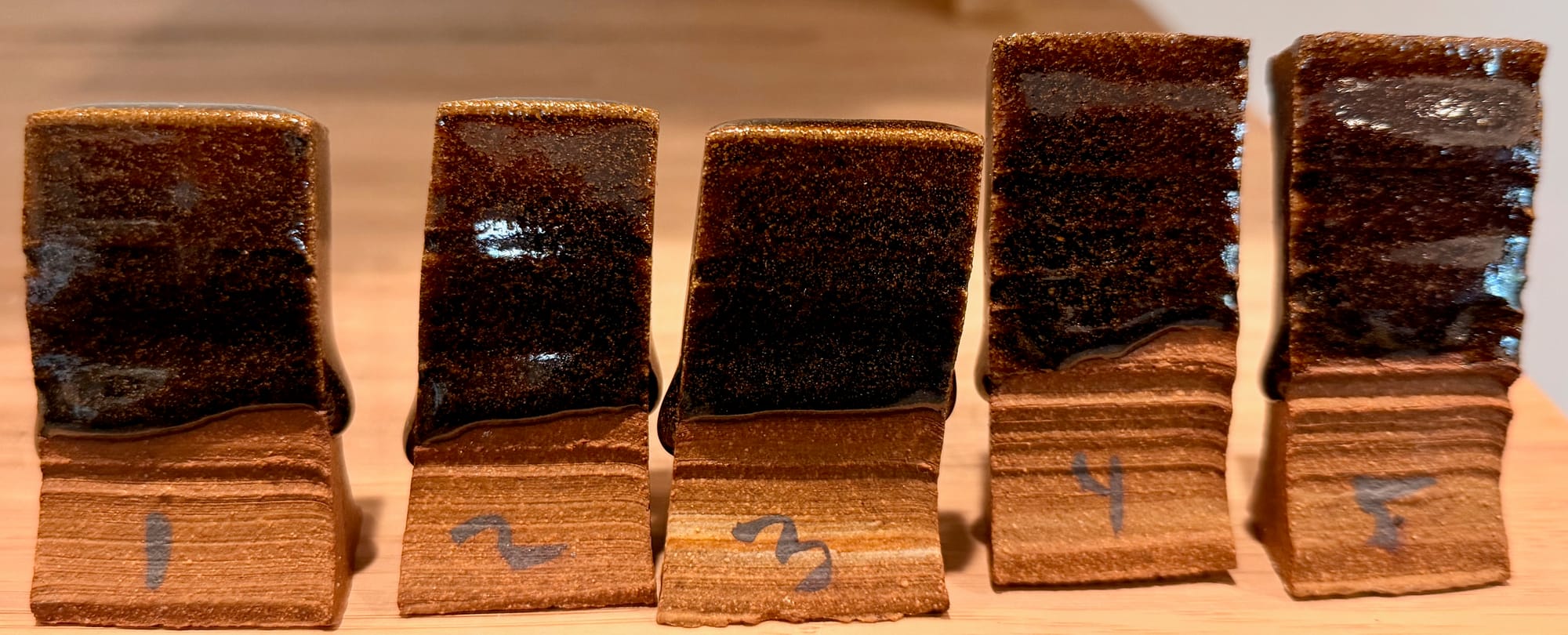

Test T53-1: In this test, 0.2% cobalt carbonate was added to the base glaze, after which copper carbonate was introduced in increments of 0.1%, producing a series at 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4%. (At these small quantities, measuring copper accurately on a triple-beam balance proved challenging.)

Even at this relatively low level, cobalt carbonate drives the glaze to a uniformly dark brown to near-black appearance, particularly in thicker areas. Within this dark field, the warming influence of copper is still visible, with increasing copper additions subtly enriching and warming the surface rather than shifting the glaze toward green or blue. The cooling firing cycle produces an abundance of micro-crystals throughout the series.

In contrast to the iron-only Tenmoku base, where color depth develops gradually through absorption and micro-crystal-enhanced scattering, the introduction of cobalt collapses the color space much more quickly. Even at low levels, cobalt’s strong absorption suppresses most transmitted light, driving the glaze toward a dark brown or near-black appearance. Within this compressed tonal range, copper no longer functions as a hue-shifting colorant but instead acts as a subtle thermal modifier, warming the surface without materially altering its overall darkness.

Although these results did not produce the black satin surface originally sought, the glazes are visually rich and cohesive, and they perform well on darker clay bodies.

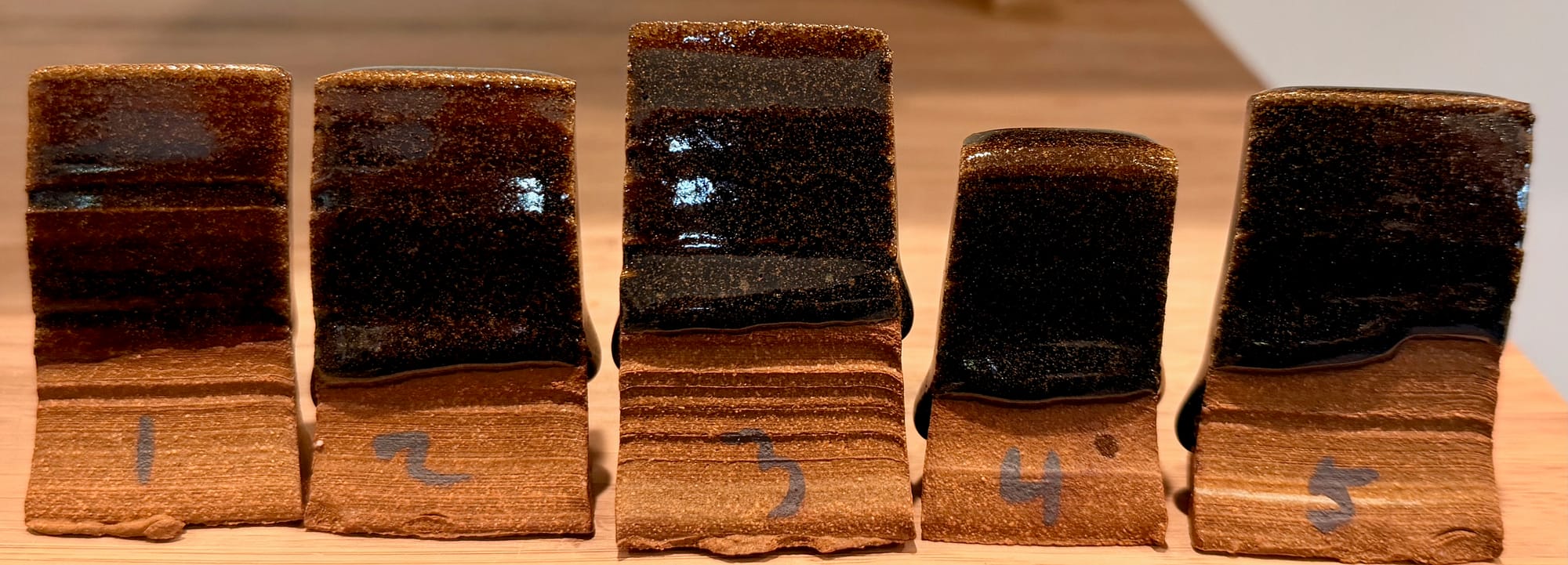

Test T53-2: In this test, 0.2% copper carbonate was added to the base glaze, after which cobalt carbonate was introduced in increments of 0.05%, producing a series at 0.05%, 0.10%, 0.15%, 0.20%, and 0.25%. (Perceived inaccuracies when weighing such small amounts prompted the purchase of a more appropriate digital scale.)

In this series, the progression of cobalt is clearly visible across the tiles. Notably, green hues emerge on tiles #4 and #5 when applied to porcelain. Aside from tile #1 on porcelain—which closely resembles the studio granite Tenmoku subtly warmed by copper—the results may not be especially compelling from a color standpoint. However, the cooling firing schedule produces notable micro-crystal development throughout the series, an effect discussed in the following section.

The Sedona Red tile #5 is shown above in close-up under strong illumination. This glaze—Base-Z with 10% red iron oxide, 0.20% copper carbonate, and 0.25% cobalt carbonate—exhibits clear evidence of both phase separation and crystallization. At the surface, translucent golden zinc-rich silicate micro-crystals have precipitated during cooling. Beneath the surface, the glaze has separated into compositionally distinct glassy phases, producing regions of differential light scattering and absorption. Within this darker iron-rich matrix, localized cobalt-bearing domains appear as soft blue, nebula-like patches. The combined effects of surface crystallization, bulk phase separation, and depth-dependent absorption create a pronounced three-dimensional visual structure that becomes most apparent under strong lighting.